Our Location

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

An ancestral hall is also known as a clan shrine, ancestral temple or lineage hall. It is a place where the spirit tablets of ancestors are enshrined and ancestral worship ceremonies are held. Meanwhile, it also serves as a venue for promoting clan traditions, enforcing clan rules and family disciplines, as well as holding clan meetings and banquets.

In modern China, the culture of ancestral halls prevails most prominently in Jiangxi and Guangdong Provinces. Among them, the architectural style of ancestral halls in Jiangxi has exerted the most extensive influence, for a large number of people migrated to many central provinces from Jiangxi during the Ming and Qing dynasties.

In northern China, due to the wars brought by the invasions of the Mongol Yuan and Manchu Qing dynasties, the Han people failed to form long-term stable inhabited villages, resulting in very few surviving ancestral halls to this day. Most villages in modern northern China are inhabited by people of various surnames. It is unlikely for these villages to afford the construction of an ancestral hall unless a single clan gains an absolute dominant status locally. The reason for this is that the site selection for an ancestral hall is extremely stringent: it must be built on a dragon vein, the spot with the finest geomantic omen in a village.

The following is a separate elaboration on some characteristics of the layout of ancestral halls in Jiangxi and Guangdong respectively.

This architectural style is widely adopted in present-day Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi, Anhui, Sichuan and other regions.

(1) Overall Style

Most of them are built with grey bricks, grey tiles and white walls, and the gable walls are mostly in the form of hard gable fire walls. As shown in the figure below:

Ancestral halls mostly adopt the “four rivers converging into the hall” layout, with a patio built inside the building. Rainwater from the surrounding roofs converges in the patio, which implies that “benefits shall not flow to outsiders’ fields”, and also facilitates ventilation, lighting and drainage. In terms of architectural decoration, ancestral halls attach great importance to the craftsmanship of the “Three Carvings”—wood carving, stone carving and brick carving, featuring rich themes including character stories, flowers, birds, fish and insects, landscapes and scenery.

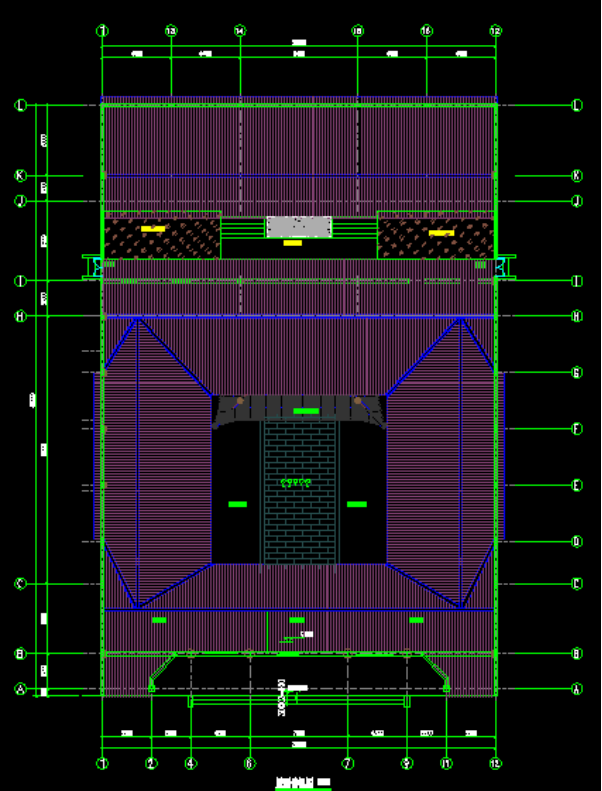

(II) Layout Plan

In terms of the layout plan, the ancestral hall is basically divided by the side door of the through hall: the front half serves as an activity area for the living, meant for liveliness and gatherings; the rear half is a sacred area for the ancestors, meant for solemnity and tranquility.

The activity area for the living is usually larger, as it is the main venue for hosting banquets for weddings, funerals and other clan events. Take a village with a population of 1,000 as an example: the hall is generally required to accommodate 30 to 50 banquet tables (10 guests per table). Meanwhile, opera performances are staged for the ancestors during festivals and lunar new year celebrations – the elderly villagers also enjoy these shows immensely, perhaps because only in old age do they truly understand that life is like a stage play. For this reason, an ancestral hall is equipped with an opera stage and seating for the audience.

The rear ancestral shrine (the inner sanctum) mainly houses spirit niches holding ancestral memorial tablets, offering tables, and percussion instruments used for ritual ceremonies. In larger ancestral halls, side rooms are attached to the inner sanctum to serve as lodging for Taoist priests and opera performers.

(I) Overall Style

Cantonese ancestral halls mostly adopt a hip-and-gable roof with grey brick walls raised on stone plinths, and their gable walls are mostly of the wok-ear style or fire-sealing gable type. For the ancestral halls with a wider facade, there are Qingyun Alleys on both sides, with inverted wing-rooms at their entrances. The grey plaster ornamentation on the main roof ridges is a prominent feature of Guangdong ancestral halls. These grey plaster ornaments boast rich themes and depict a variety of forms including human figures, flowers and birds, as well as auspicious beasts, as shown in the figure below.

(II) Layout Plan

Ancestral halls in Guangdong generally adopt a building pattern of three bays and three courtyards, meaning the building has three bays (in the width direction) and three deep sections (in the length direction). Along the central axis are successively arranged the main gate, patio, central hall, rear sleeping quarters and other structures, with verandas, Qingyun alleys and side ancestral halls flanking both sides.

The entrance of an ancestral hall features a porch-style layout. Xumi-style base platforms (commonly known as Diaoyutai/Anglers’ Platforms) are usually built on both sides of the main gate, where musicians play music during sacrificial ceremonies and celebrations. Smaller ancestral halls, study halls and private schools mostly adopt the traditional concave entrance form of Cantonese folk dwellings for their entrance design.

Although ancestral halls vary in style from place to place, they share many common features in their overall layout, which can be generally divided into several parts: the square in front of the gate, the opera stage, the main gate, the surrounding walls, the patio, the Xiangtang (Hall of Worship), the Baitang (Hall of Tribute), the Qintang (Ancestral Shrine Hall), and auxiliary rooms.